by Chitto Ghosh

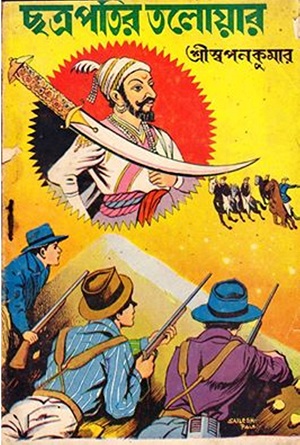

I had a collection of the one and only Samarendra Nath Pandey alias Swapan Kumar’s trend-setting crime pulp fictions—120 of them, written between 1953 to the early ’80s. This primarily includes the Crime and Mystery Series, Kaalrudra Series, Biswachakra Series, Rocket Series, Dragon Series, Kaalnagini Series, Baajpakhi Series, Kaalonekde Series and others. More and more series were made identifiable with the name of the villains—Kaalrudra, Dragon, Kaalnagini, Kalonekde, Baajpakhi, etc. Dipak, his charismatic indomitable super sleuth from an upper-class Brahmin family, is a private detective working in Kolkata—although some of his cases take him across India, and even to China. He has a scientific bent of mind—a laboratory in his house to carry out tests relevant to his investigations, and is adept at firing two revolvers in two hands at a time—ambidextrous a la Arjuna, indeed.

Swapan Kumar is, in no way, the original guru of Bengali deshi (whose honorific is Bot-tala) pulp fiction, but certainly, the most-read high priest of the genre. The prolific writer that he was, he produced other genres of works in his other avatars. He was Adi Shree Bhrigu with an alternative pseudonym of Jyotishi Shri Bhrigu, an astrologer, and Dr. S. N. Pandey, an author of several books on self-medication. Going by a version in circulation in our youth, Samarendra Nath was a medical student and he started writing these fantastical crime fictions to offset his educational expenses. He hardly cared for the logical build-up of the narrative that detective stories and novels ask for to tease, intrigue and engage the readers—but the lacuna did not stand in his way of creating a universe of young readers cutting across the urban–rural divide. He also wrote a couple of popular books on nature and cures of “Gupta Jouna Rog” (stigmatic sexual diseases) under his real name.

Swapan Kumar, for his huge popularity, had multiple publishers of his books—mostly unknown—and about half of them disappeared long back for reasons one can easily guess. Therefore, the exact numbers of his books are difficult to trace and count. What has compounded the counting is repeated publishing of the same novellas between new covers, with a fresh look that often misled his loyal readers, like me, into buying the same book more than once. Nearly half of his bibliography came with two common catchphrases— “For College Students” & “Strictly for Adults”—to hit the bull’s eye. These two brain seducers wooed his readers, mainly young lads in the age group of 14–20 years, to pick his books priced between 50 paise and Rs 2, depending on the number of pages—which again ranged from 64 to 96 pages. The so-called class toppers and the bright college students were his readers, too. His use of sex and violence was never explicit by any standard and could hardly be termed as obscene, but for a brief yet crisp description of the young female characters that, at best, went on to talk about their undressing. This was the maximum limit of adult content that the writer indulged in to give his young male readers an additional adrenaline rush.

The genre Swapan Kumar belonged to has a history that started in Bengal with Priyanath Mukherjee, a retired police officer in British-India, who published the first-of-its-kind crime and detection stories in the series of Darogar Daptor (Police Officer’s Office—in a suggestive translation) way back in 1894. He was also the pioneering mastermind of publishing the same story between newly illustrated covers, thus setting a tradition of deception or deceit for generations of gullible readers to fall prey to. It happened as neither Swapan Kumar nor his predecessors in their genre had any access to public libraries that could have, in turn, provided data about the dates of publishing and other details. Swapan Kumar and his likes in the Bot-tala Era took advantage of their lesser known or unknown publishers’ unethical business practices.

His primary works are grouped under independent series of fictions, interestingly branded with the names of underground dons, who were routinely challenged and chased by none other than his superhero, Detective Dipak Chatterjee. But the whole idea of branding the series at a spectacular pace was an after-thought. Initially, the stories would come out in assorted order and as they were put on display by book hawkers on the streets of Calcutta, they took little time to sell like proverbial hotcakes. This craze triggered the birth of the series. Each book in the series, on its back cover, had mention of the next book with an illustration. The publicity strategy worked unfailingly to sustain the curiosity among his loyalists (in fact, there were not many casual readers of his books).

Coming back to Dipak Chatterjee—a hyperpolygot, trained in the martial arts, with an impeccable command of firing a pistol at the target flawlessly, he was, in some edge-of-the-seat-moments, described to be carrying two pistols in both hands and a dagger! But I, at least, had no time to be perturbed by such funny flaws, as the pace of the narrative did not offer much of a breather to brood over them. Usually ‘Watson-ed’ by Ratanlal, Chatterjee also gets help from his female assistant, Tandra, and his young student, Rajat Sen. Chatterjee’s Lestrade is Inspector Gupta. Chatterjee takes on a wide range of criminals, from femmes fatales to mad scientists to dacoits. Many of these names have deliberate allusions to the names found in Indian Puranas and oriental mythologies, although none of them have any supernatural powers. They are Kaalnagini, Kaalrudra, Biswachakra, Dragon, Bajrabhairav, et al. However, Swapan Kumar did not make his superhero invincible, as in many of his tales Dipak’s challengers, who are endowed with cunning intelligence escape, more often than not, from Chatterjee at the last encounter or from jail. They are, like Dipak himself, masters of disguise. Many of Kumar’s bad boys and girls are Robin Hood-styled outlaws. In the novella, Prithibi Theke Durey (Away from the World), one of Chatterjee’s enemies, the master-thief, Bajrabhairav, teams up with a mad scientist to break a novel kind of war to conquer the world. The scientist has created a force field impervious to all forms of counter-attacks—even by the military superpowers of the world—and intends to use the force to disarm them without much bloodshed and establish a Utopian world.

Dipak was neither a James Bond (who was essentially a spy, not a detective), nor a Jason Bourne by any stretch of the imagination. But going by his modes of action and physical agility, he appeared to be, in a way, a blend of both without having their cutting edge gadget-driven sophistication. The similarity was not inspired by these iconic western thriller heroes as Kumar, I doubt, was not acquainted much with the writings of Ian Fleming (who, incidentally published his Bond novel in 1953) or Robert Ludlum, or for that matter anybody in their league. Closer home in Bengal, he had two stalwart detective writers around in the then mainstream literature—Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay and Dr. Nihar Ranjan Gupta, with their Bymokesh and Kiriti Roy stories, respectively. Both of them were not only distinctly different from each other, but also in their styles of detection. Byomkesh was by far cerebral, while Kiriti was more of an action hero, loosely inspired by Hercule Poirot. Swapan Kumar, the poster boy of Bangla literature’s counter-culture in his time, did not follow any structured approach of storytelling knitted by some sort of narrative logic, save the logicalities of actions described. He, in fact, did not care much about these academic finer points. He was not cut out for it, nor made for the discerning readers either. He was, in a way, a forerunner of B and C-grade Bollywood action potboilers, spiced with crude fantasies. Kumar made no bones about it. He made a wide range of characteristic variations among the villains, too. Baaj Pakhi (The Eagle), closely followed by Kalnagini (The Queen Cobra), topped Kumar’s merit list, who mostly managed to hoodwink Dipak and escape after every breathtaking encounter, leaving the writer with yet another chance to churn a sequel or the next novella in the series. The most characteristic feature of these series is that the Dasyus (master villains) like Dragon, Kaalrudra, etc. are not traced till the very end. In the stories of a given series, Detective Dipak succeeds in tracing the dens of crime along with their motives, but not the criminal masterminds. Each time they escape at the last moment, and often the story ends with a common sigh of frustration by Detective Dipak and police inspector, Mr. Gupta. The logic of sustained calculated marketing (that the criminal might escape in this volume, but he/she could be arrested at the end of the series) also didn’t hold good here. The series, too, concluded with these villains escaping unhurt and leaving a letter addressed to Dipak. The letter would usually read that it was not easy to catch him/her. Dragon and Kaalnagini were arrested once and were sentenced to death after the trial. But the author in Kumar was so much in love with them that he offered them leeway to escape from the gallows with the help of some criminals dressed as the police there, or through a secretly dug tunnel under the well. Some noteworthy characteristics of these villains are as follows:

- They are always in disguise, so nobody knows how they look.

- Even in meetings with subordinates, the masterminds come with a mask covering their face, or provide instructions via radio signals.

- Often after the crime, like robbery, theft, murder, etc. they themselves give intimation of their crime, either over the phone or by letter, to the Police HQ.

- They admire Dipak Chatterjee for his sharp crime detection skills, but at the same time, throw challenges to catch them if he can, with clear conviction that he wouldn’t be able to. Dipak, too, has reciprocative respect for his wily bête noirs.

- Some of them, like Kaalrudra or Kaalnagini, are the Robin Hood-types. They rob from the rich and powerful and help the hapless and the poor. In one story in the Kaalrudra series, the news of Dasyu Kaalrudra’s death by an unknown mercenary hits the headlines of newspapers that praise the benevolence of the outlaw and go critical of the police’s role in maintaing law and order. The news is later found to be a rumour.

- Other than these author-backed outlaws, there are criminals with a linear mindset of unleashing cruelties upon the rich and the poor. Kumar sets the moral standards even a few notches higher for some of his more benevolent outlaws by secretly helping Dipak to arrest these criminals. Moral warfare consciously created by Kumar.

- At times, by just seeing the financial condition of the victim of the crime, or the degree of cruelty associated with the crime, Dipak is sure that the crime was not committed by his crafty bête noirs. It further corroborates the same moral differentiator.

- In some cover illustrations, like that of Ajana Dwip-e (On an Unknown Island), Akashpathe Dragon (Dragon in the Sky), the good-at-heart images of the outlaws are subtly portrayed. Dragon, shown as a benevolent despot, takes his gang to a virgin, un-manned island in the Bay of Bengal after being chased by the police and Dipak. There he establishes an Utopian society, where everybody would work and get their share according to their needs. They are told to abandon enmity and to iron out all differences among themselves. On a serious note, it is not difficult to find a direct connection between the usage of the ‘mythical’ names for the villains that ask for sympathetic calibration of the ‘morality’ of the outlaw. There are other stories that can also be cited as examples of such acts.

- I found a sci-fi story in the crime thriller format by Swapan Kumar—Prithibi Theke Durey (Away from the World). Bajrabhairav, the outlaw, has joined hands with a scientist during the Second World War in a remote area in Burma (now Myanmar), who had invented an automatic tri-footed instrument immune to bullets, grenades or bombs. When Dipak, at the request of the Governor General, goes in to investigate, he is caught and imprisoned by Bajrabhairav. There he sees the same high moral standard of his adversary when he confides to Kumar’s detective about his real intentions behind the invention. It was for defeating all the war-mongering nations in the world to establish peace on his own terms.

- The crimes committed in the Dipak Chatterjee thrillers are limited to murders, dacoities and gang wars which are, by and large, acts of vengeance against some incidents of injustice and betrayals committed in the past.

- Black Ambassadors are the cars chosen by Kumar for his master villains. Kumar, I believe, did not go by the evil connotation of black, as the colour is often used as the symbol of power and influence.

If this aspect of morality associated with crime is one of the central features of Swapan Kumar’s stories, then one can trace a long tradition of “moral criminals”, starting from the early-Colonial period. In the 1830s, a memoir of a thug (Amir Ali, convicted for 719 murders) was written by Colonel Meadows Taylor in a book named Confessions of a Thug. I have managed to get a Bangla rendition of the book called Thagi Kahini, written by a police officer, Priyanath Mukhopadhyay. The life of that thug, Amir Ali, was spared because he acted as an informer to the British Government, who went all out to end the thug anarchy in then-Bengal, led by Colonel Sleeman during the Raj of Lord William Bentinck. Interestingly, as the memoir of Amir Ali unfolds, one can see that diverse thug groups were earnest devotees of Devi Bhavani or Kali, and followed a distinctly different religion or dharma called “Thag Dharma”. Even Amir Ali, despite being a Muslim, was a sincere devotee of Goddess Kali. The philosophy of their religion that centres around the killing and robbing of people have it that in the beginning, when Lord Brahma created the Universe and all living beings, Lord Vishnu took the responsibility of nurturing them. As there was no mechanism for destruction back then, the continuous creation and nurturing led to an imbalance in the Universe. Finally, Lord Shiva was assigned the job of destruction, but he agreed under the condition that he could only do it by the order of his consort, goddess Bhavani. The thagis, being the devotees of Bhavani, took upon their shoulders the task of taking the lives of those who, according to them, were ‘sinners’. They believed that no sin would harm them if they commit the killings without being driven by worldly passions. They performed elaborate rituals when a new member was baptised to take up Thagi-dharma. They also had elaborate taboos in their faith, such as the killing of lower-caste people (like washermen, iron-smiths, oil producers, etc), performers (singers, dancers, roadside tricksters), followers of Bhakti–Sufi cults (like people following Sikhism and Nanak-sahi, Fakir), patients of incurable diseases (like leprosy) and finally, women. According to the account of Amir Ali, the Thagi Dharma was well organised with codifications done in a language only a Thagi could understand, and all those under the religion were considered equals. The belief was so strong in Thagi Dharma that a Muslim thagi didn’t hesitate to take a false oath touching the Koran. At the end of his confession, rather the narration of his life, Amir Ali said in a despising tone to the English officer who was taking notes of his statement, “You Sahibs are truly extraordinary. You have the ability to make the impossible possible. You can convert a braveheart thagi like Amir Ali, a victorious leader of thagis to whom thousands of thagis look up for their lives and livelihoods, into a traitor. I am now betraying them by surrendering myself to the treacherous planning and whims of the English officials who are out to uproot the thagis.” And finally, Amir Ali succumbed to mental illness from this betrayal. The last part of Ali’s comment provides an important clue regarding the conflict between ‘‘alternative morality of criminals’’ and the new ‘morality’ of British rule. In the several oral tales about the robbers of Bengal—compiled later in the book, Banglar Dakaat—the propagation of similar pre-Colonial moralities can be found, which went on to shape popular fascination for these outlaws.

Swapan Kumar was, in his own manner and with his typical idiosyncrasies, a flag-bearer of this morality.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Chitto Ghosh is an advertising writer by profession who runs TalkingTree Communication.

Good article. Brings back memories of schooldays though I was not that much of a Swapan Kumar buff . Probably read around 4-5 books. The article is a little long though.