by Subhojit Sanyal

Rituparno was no ordinary man, he was just no ordinary creative genius, he was much more than just the reasons he was popularly known for. Rituparno Ghosh was a brave genius. He dared to dare. Everything.

I went to Rituparno Ghosh’s school till class X, but of course, I had no clue who the hell Ghosh was. Bangla films were always a non-entity for me. It was a whole language barrier, but that we’ll get to another time. So, by the time I was 14, we started to hear our parents discuss a movie called Unishe April (19th April). I never got it, I never bothered to get it. Even when I saw some glimpses of it here and there, it was too boring for me. Now I was in American mode. Fights, more graphic sex scenes than imaginable in Indian cinema, and entertaining—what more can a 14-year-old ask for.

Now it was when I was 16, I chanced upon it one more time. It was just starting on some Bangla channel on TV and my mother was hell-bent on watching it this time. So I think, what the heck… let’s give it a shot!

It was after the first 10 minutes that I start getting more and more interested in what’s happening. This was Bangla cinema?? My mind was reeling. I felt like a fool. This was amazing. It was so real, the people were real, people we might know, people who actually live and breathe. I couldn’t help marveling at the simple, yet complicated plot either. Who would have thought? A relationship between mother and daughter, and everything that happens between them in that one night. Simply amazing.

Ghosh made a convert out of me. How couldn’t he? I followed up with Shubho Muharat, one of my all time favorite mystery films, Utsab, a simple tale of love and relationships in one large Bengali family that have reunited for the Durga Puja. Ghosh’s script was strong as usual, his story was largely simple on the face of it, revealing itself bit by bit as the story gained momentum. Over the years then, I went on to see mostly all his movies. Be it the compelling Baariwali, his magnum opus, Chokher Bali, Ghosh’s take on matrimony and relationships in Dosor, or the tale of two very different women in Dahan, I saw them all over repeated viewings.

And every time I watched one of these movies, the one thought that always struck me was the way in which he handled his women. Much more than the men in his movies, it was the women who always had the greatest substance, the women always went against the grain, and I can say confidently, his women were real women, his women dealt with their issues, they thought outside the box even though they more or less remained within their social mechanisms. For instance, Rituparna Sengupta in Utsab wasn’t one bit happy about receiving the divorce notice from her husband, but she doesn’t sink away with it. She continues to stand up against her idealistic, moron of a husband. She accosts him, she doesn’t use herself as a doormat for him to walk all over her.

It’s more or less the same thing in all of his movies. Take for instance, Dahan. Rituparna Sengupta is teased and groped by some men, while everyone else looks on. As she struggles and screams in protest, Indrani Haldar jumps out of an auto she was using and goes on to ward off the molesters and bring back some order in the chaos. And while she may have done something brave and courageous, it doesn’t sit with the men in the lives of both women. The eternal problem of “why get involved?” and of course, the men realizing that the women don’t need them for anything in their lives. The particular scene where Rituparna confronts her irate husband who needs to re-emphasize that he is the man in the house, that was simply spectacular and something that only Ghosh could have presented to us.

And while I cannot go about commenting on each of his movies, I must make special mention of Shubho Muharat. Dealing with a murder, the root of which is discovered to be at the inauguration of a new movie, the movie has three principal female characters, while the couple of men in the movie acting merely as supporting characters. Inspired from Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple series, Shubho Muharat was a first in Indian cinema.

Rituparno went on to include Hindi and English films in his range as well, both scripts he was extremely comfortable in. Raincoat in Hindi, starred Ajay Devgan and Aishwarya Rai, showing Ghosh’s growing popularity on a pan-Indian scale. The Last Lear, Ghosh’s maiden and sole English feature starred the legendary Amitabh Bachchan in the role of a lifetime. While on the topic, I must add that The Last Lear must be one of Ghosh’s only films where the male character took the center stage (while that must have been catered more to the actor than Ghosh’s own sensibilities). There was also speculation at one time that Ghosh wanted to make another Unishe April with Amitabh and Abhishek Bachchan (who had already worked with Ghosh in the period social-drama Antarmahal, switching the mother–daughter storyline to a father–son storyline. For those who have already seen Unishe April, Ghosh’s casting for the father and son were stellar and near-perfect, but I for one always wondered whether he’d be able to do justice to a male-centric narrative. Of course, I must have been wrong, but that was just the impression I had of Rituparno Ghosh.

And at the age of 49, with the post-production of his latest Byomkesh Bakshi mystery feature still pending, Rituparno succumbed to a massive heart attack. And thus ended, one of the most dominant phases of Bangla cinema and the collective contribution of Indian cinema to the world.

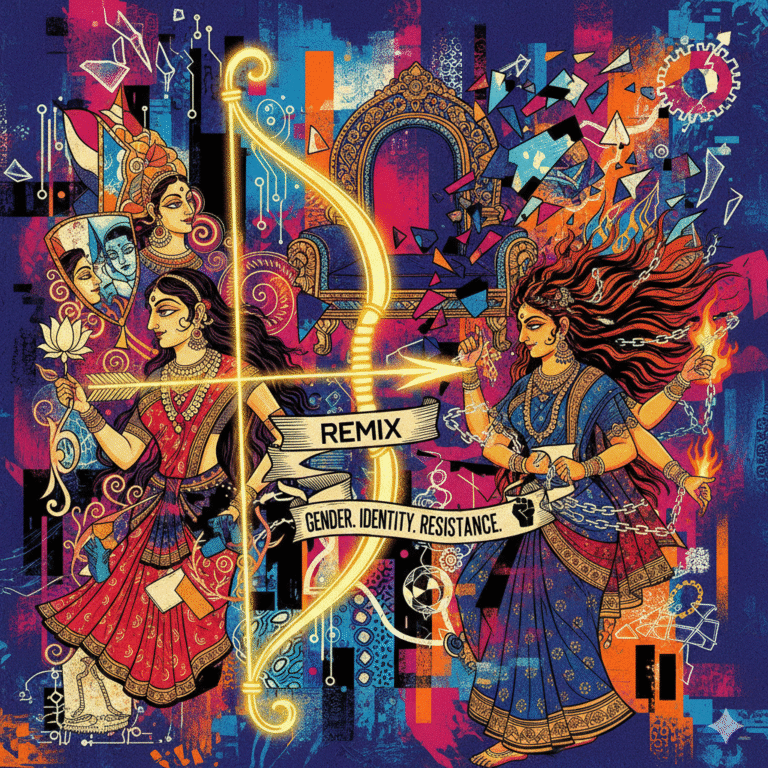

What Ghosh gave us was the narrative, he gave us believable yet exceptional characters, he single-handedly documented the position of women in Indian society, right from the colonial times (Antarmahal) to the modern (Dahan). His personal life/sexual preference was hardly a matter of debate and it is little wonder than Ghosh understood the psyche and motivations of women way more than the male-centric Indian film industry.

And we’ve just been talking about his films. Rituparno Ghosh was far more than just that. He was an advertising professional, with his famous line for Boroline achieving immortal status (Shurobhikho antiseptic cream, Boroline), he was an economics graduate and he was a rebel, because he was the person who society does not accept easily. And towards the end of his short and exemplary life, Ghosh finally gave up the facade and presented himself to the world in the way he wanted to. He became much bolder with every passing day, he faced brick backs and snide comments from the average conservative, dogmatic, ritualistic, religious Indian—but he did not stop. He continued to dominate the Bangla film industry, he continued to make spectacular movies with love and affection, he continued to challenge the medium of cinema and he forced people to take note of him. With his death, the LGTB community has perhaps suffered the most, for he was their poster boy, he was their brand ambassador, he represented those who still couldn’t find their voice to reveal themselves. He made himself the prototype of all LGTB people in the country. In this country, that takes a lot of guts.

And that is why, his passing away just wasn’t the death of a man, no he was a complete human being, he was the perfect blend of a man and a woman, and he stood his ground proudly, even as people flinched. He did not find it necessary to constantly defend his actions (I don’t think he ever gave an explanation for how he looked or spoke) and he continued to make movies at a steady pace, each one of them better than the last, each one of them a classic.

He will forever be missed, so great is his contribution to cinema, so courageous is his contribution towards moulding a new, secular, tolerant Indian society. His immense sacrifices, his fight cannot go to waste now. Someone has to take it up from where he left off. Bangla cinema has to veer herself back to his works, and Indian society needs to carry on from where Ghosh’s death left them. He will be missed, for many more reasons than one.

+ There are no comments

Add yours