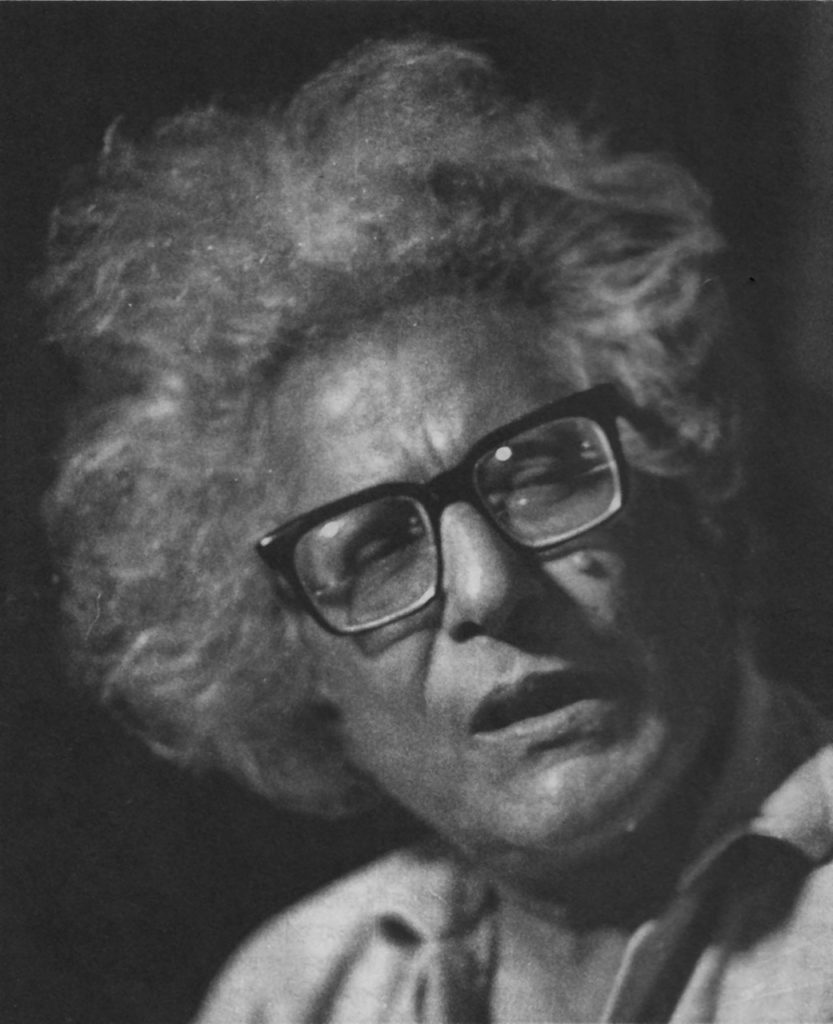

This is the centenary year of Bangla poet Subhas Mukhopadhyay, whose works have inspired almost two generations of Bengalis, particularly, the ones with a Left orientation. Many of his lines have, on one hand, inspiring while many have been a part of daily quotable quotes. Despite his differences with the Communist Party of which he was a member, he continued to command respect and admiration from the vast middle class Bengali intelligencia.

Chitto Ghosh, an advertising writer by profession who runs TalkingTree Communication has discussed the life and works of Kobi Subhas for Art Pickles blog site. All poems of the poet that feature in this blog have been transcreated by the author.

The photographs accompanying the article have been sourced from various published sources.

It is a worthy tribute to the poet of the subalterns.

Son has gone to the forest

Cheley Gechey Bon Ey

(1972)

Ram went into exile in the forest

Dasharath, the dad

with his broken heart,

died within 6 months flat.

It’s startling to wonder

How did Valmiki survive through the millennia

writing the seven kandas of Ramayana

based on such boring trivia.

If I shall ever write

To make the destiny obey my order

I shall not drag the blind sage, never ever.

The thought of writing brings to mind an extinct desire

Of becoming a writer

with a remote passion for shooting a sound maker

( I also was, then, a chaste by far)

Ram, Ram…what a shame!

Pardon the inane act of this minion, Oh Lord.

The utterance of ‘shooting the sound maker’

is only an unwitting slip of the tongue.

Shooting an arrow at the gurgling sound of filling a pitcher

I didn’t kill anyone by mistake

I am not cursed by any blind sage.

Baring my heart to the public I don’t show the stains of my tear

I am not the one to go by the curtain lecture

Hey, that tormented highly strung henpecked Ikskakkhu dynast-king

Keeping my mouth shut I bear the brunt of that ancient sin.

When my time comes to retire to Vanaprastha

Leaving me tied in the worldly bind

My son has gone to live in the wild

But I am still a foot soldier, the drum in my hand beats for war –

Ratnakar, come closer to me; you get lost…Valmiki.

2

Sweat is mumbling on the forehead

Time stands still

Like a halted tram

with its overhead wire torn to reel

Leaving me tied in the binds

Son is out in the wilds

To fight the war for freedom.

In the next table, a tippler

has gone into the state of trance.

I am keeping a strict vigil on my bottle of soda

With a vow of not loosing my balance.

Today, forshaking all the worries

I will join in the company of my good ol’ memories.

If I miss the bus to home

Shoving the paper boat

I will go all the way by foot

Letting the hands carry my boots

I will go sprinkling the dews all the way

Taking no care of the threats by the tall waves

on the raging river that’s burst its banks

I want to get back all the marvels of my boyhood days,

the thrills of walking through the dark nights in the light of hand held lantern.

Leaving me tied in a bind

Son has gone into exile.

Knowing well that he was not at home

Police came in two vans at one midnight

Poniting their guns at me they searched every nook and cranny

Well into my 40s, shaken by them

I feel the dousing fire in me kindling bright

once again.

Still today I rush to the roads to see in awe every procession pass by

I go to any public meeting only to hear

the speeches the speakers deliver.

I consent to every good works done by any body

For being tangled in family chores I do not light the fire.

Leaving me here in the binds

Son has gone to the wilds

Although I have seen flying free on his palm

My own flag

That’s been crowned in the youth’s kingdom

Nothing could be more momentous for a poet than to set out on a journey that would end up being a unique chronicle of a literary legacy India has to celebrate time and again. Subhas Mukhopadhyay, a Bengali by birth and linguistic identity, announced his arrival with ‘Padatik’ (‘Wayfarer’) when the young Turks in Bangla poetry had bet their creative energy on their mission to get out of the influence of the millennium’s most formidable poet-genius, Rabindranath Tagore. The year was 1940, a time in history seething in death, destruction and devastation due to World War II. The preceding decade, sunk in the quagmire of prolonged economic depression, had engineered the rise of the Third Reich, led by one Adolf Hitler. The time reflected “…the age of anxiety” according to W. H. Auden’s observation. Rabindranath, one of the world’s most revered polymaths and an untiring peace campaigner, despite putting himself in self-ejecting mode, had written a masterpiece in his inimitable style, titled “Crisis of Civilization”. He said, in no uncertain terms, “…losing faith in man is a crime”. A couple of months later in January 1941, confined to his sickbed, the poet made a confession about his limitations and expressed his solemn intent in the poem, Oikotan (Chorus), “Je acchhey matir kachhakachhi/ Ami se kobir lagi kan petey achhi” (The poet who lives close to the real world/ is one I have been all ears for).

At this juncture of history, with his eyes and ears open to the ongoing millions of mutinies across the world and the nation, driven by anger, despair, challenges and rebellions, Subhas embarked upon his journey. By then, Kallol’s emphatic emergence had jolted and jerked the system of stagnant societal values and anachronisms. It gathered young writers who were in search of their identities through post-War uncertainties. The consequences of war were so alarming that the entire Western world had plunged into anarchism, from which even the sensitive minds of this country could not escape. Predominantly influenced by Marxism and Freudian thoughts, the Kallol writers boldly protested against a society harbouring medieval orthodox conservatism.

The most notable debate that Kallol initiated was on the necessary transition from the traditional to the modern, from the lyrical poetry of conformist writers—mainly from the older generation—to experimental genres by non-conformist younger writers. The debate got so fiery and intense that Rabindranath, who was respected by both camps, was drawn into this discourse, too. Central to the debate was the direction Bangla literature should move in. In March 1927, Rabindranath took the chair over the two meetings between the warring camps. He proposed a compromise, only to be summarily rejected by the progressive camp. The intellectual parley that followed in literary journals shaped a whole new narrative.

The cultural and intellectual tension thus surfaced led Rabindranath to challenge his genius—arguably for the last time in his life—and he came up with his self-critical masterpiece, Sesher Kabita (1928), as an anti-thesis to Kallol writers’ unorthodox literary pursuits and subsequently, an enduring bouquet of gadya kabita (free prose poetry) —though, the movement to him was “poverty combined with the unrestraint of lust.” All put together, the Kallol that came into existence as a magazine launched by Gokulchandra Nag evolved into Bengal’s first conscious literary movement with a galaxy of new talents like Premendra Mitra, Bishnu De, Sudhindranath Dutta, Ajit Dutta, Kamakshiprasad Chattopadhya, Manish Ghatak, Dinesh Das, Achintya Kumar Sengupta and Samar Sen amongst many others. They re-defined and re-invented Bangla literature by expanding its horizon to deliberate on the angst and pangs of the people hitherto neglected. Yet, in style and approach to poetry, they were distinctly different from each other. But the poet who single-handedly steered Bangla poetry into a whole new multi-layered realm of creative insight was Jibananda Das. Intellectually, they were influenced by Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud and Soviet Communism; creatively, by Charles Baudelaire, W. B. Yeats, T. S. Elliot, Ezra Pound and so on so forth. Dalit literature, too, took its root in Bengal during this period.

Kallol’s end was offset by the emerging dominance of Kabita, a brainchild of Buddhadeb Basu and a magazine dedicated solely to poetry.

A twenty-odd year old Subhas, one of the original jholawala activists with a head-full of cumulus hair thundered in the spring:

May Diner Gaan

Today is not the day for playing with flowers, dear

We are face to face with destruction

Eyes have no winey blue dreams any longer

The scorching sun sears the skin off.

Hear the conch’s siren from the chimney mouth

The hammer and sickle are singing aloud

Legions of lives braving death

Long to love life with zest.

Give the dowry of your love to every bonding

Come, pledge to fight tooth and nail

The bondage will crumble in the rhythm of rising

Brighter days are waiting at the end.

The tear of the oppressed for centuries of torture

Putting every breath to shame

No more cowardice and living in fear

Wear the armours for war and be game.

Today is not the day for playing with flowers, dear

There’s come the news of destruction

Let the roads go blurred in the rough weather

The soul of youth will find them spot on.

Was he the poet Tagore had been waiting for? Maybe, maybe not—although Subhas, like him, posited his faith in man, especially those who constituted the majority—hapless, homeless, landless, jobless and oppressed always. Ones who had been waiting almost unconsciously for someone who would bring to the fore their seemingly endless sufferings in the language they could understand. Tagore desired it and Subhas arrived with this mission. He made his poetry his own manifesto. But Buddhadeb Bose greeted him with reservation— “Subhas Mukhopadhyay is a craftsman in both meters—three syllables and poyer…[but]…has quite succeeded in asphyxiating the poet in him with the gas of political propaganda.” Subhas was undeterred by such criticism. To put it precisely, it isn’t easy to write three-syllable-poems and Subhas, while excelling in it, imparted new sensibilities with an optimistic message of revolution. In his poetry was found Wordsworth’s “…living language of man.”

The Padatik poet was of the opinion that he could never write unless he kept his finger on the pulse of the ordinary people—both literally and figuratively. There was hardly any poet who wrote in a language so idiomatic before him. He heralded his own genre that marked a clear departure from the Kallol poets; and his distinctive, direct voice laced with flawless metrical skill and a radical Marxist worldview carved out a niche for him almost instantaneously. In his poetry, Subhash emphatically underlined the massive upheavals that were leaving Bengali society, from top to bottom, in tatters.

The decade that began with World War II continued to be rocked by a long list of genocides brought about by famine, partition, communal riots and mass emigration—to name a few. Subhash delved deep into the wounds and agonies of a time that was flitting from one disaster to another, wielding the two-edged weapon of poetry and commitment to pro-people political activism in order to deal with the all-pervasive despair and disillusionment of the silent suffering majority. Little wonder there was politics in his poetry, but he exercised a nuanced restraint to make them overtly political. His hallmark was the economy of expression and the grasp of ground realities seen through the prism of Marxism with no string of dogma attached. His radical activism continued unabated. He was one of the founder activists of the “Anti-Fascist Writers’ and Artists’ Association”, formed in March 1942 in protest of the murder of Somen Chanda, a fellow-writer and Marxist activist in Dhaka. He obtained his party membership that same year, which took him closer to an impressive flock of profusely talented left-leaning authors, actors, artists, musicians, playwrights, would-be-film-makers and teachers. This association, in due course of time, proved to be the ‘tempus potentum’ in the cultural history of India.

On the personal front, tall, dark and handsome, Subhas was known to be very close to the ailing Sukanta Bhattacharya, a rising Nazrul-like phenomenon in Bangla poetry. Subhas did everything he could to manage the cost of his younger friend’s treatment, who penned, among many immortal poems, Runner—the poem later composed into a timeless musical narrative (as it was more than a song) by Salil Choudhury. Incidentally, the artist whose voice immortalised the song was also his buddy—Hemanta Mukhopadhya. It was Subhas again, who played a lead role in converting Hemanta from a writer to the doyen he later became. Sukanta succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 21, possibly leaving Subhas more resolute in his resolve to raise his poetry to a continuing ‘narrative’ of the marginalised life lived by millions of farmers, share-croppers, landless labourers, mill and industrial workers. The Famine of 1943 impacted him, as it did his peers. His Swagat turned out to be poetry’s answer to Chittaprosad and Jainul Abedine’s art, the masterly documentations in painting.

During this time, the historic IPTA movement dedicated to India’s cultural awakening also hit the Indian subcontinent, which bolstered the impact of the Quit India movement at some levels. All in all, it was the nation’s exposure to Dickensian dialectics: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity.”

Post-independence however, the Communist Party of India went underground after being banned by the Government of India for its indoctrinated slogan of “Yeh azaadi jhoota hain” [This freedom is false] in 1952. Subhas, along with Abdul Razzak, Satish Pakrashi, Parvez Shahidi, Charu Majumdar, Girija Mukherjee and Chinmohan Sehanobish faced arrest.

Subhas, a Philosophy graduate from Scottish Church College, stepped into the big league of Indian literature with his book of verses, Chirkoot, in 1950. The combination of a powerful poet and an unpretentious political activist made his popularity graph soar. Dubbed as “the romantic decade of nation building”, the 1950s saw creativity across literature and all domains of the performing arts surging full steam ahead, getting more dynamic, vibrant and experimental. It was a happening era with hordes of new talents churning out the plethora of masterpieces that, in turn, linked Bengal to the global mainstream of modernism. This time around, Jibanananda Das, the key architect of this uplift died of a suicidal tram accident, leaving a gnawing vacuum. A year later, ‘Kirttibas’, a poetry magazine led by Sunil Gangopadhyay, Ananda Bagchi and Dipak Majumdar kick-started to showcase new poetry by the then-new generation, letting ‘Kobita’ lose its steam. The poets, besides Sunil, who emerged to reign supreme continually in the decades that followed were Shankha Ghosh, Shakti Chattopadhya, Biren Chattopadhyay, Sharat Chattopadhyay, Ram Basu, Benoy Majumdar, Manindra Gupta, Utpal Bose and Tarapada Roy, among others.

Kabita Sinha was, possibly, the first woman modernist to break the glass ceiling. And right then came one more blow to this buoyant atmosphere—Manik Bandyopadhyay, one of the legendary ‘Banerjee Triumvirate’ in Bangla literature and Subhas’ ‘counterpart-in-prose’ passed away, leaving a burly legacy that was soon to be shouldered partly by Samaresh Bose. Subhas, who became Manik’s close friend at the eclectic rendezvous at the office of ‘Parichay’, a legendary leftist literary magazine, composed an elegy with few parallels in the history of world literature:

Pathorer Phool

Take away all the flowers

They hurt me.

The wreaths in heaps harden into a hill

The flowers in heaps harden into stone

Take away the stone

It hurts me

Now, I am no longer

the robust young man that I was

Not the sun, nor rain, nor wind

this body can

put up with none of them

Keep in mind

Now I am my mother’s dearest son

who will melt smoothly.

Taking your leave

I have been out since morning

On the way, the evening has descended

What for you stop me again on the road?

After a long halt

The van moves pulling random breaks

People fill the flower shop at the crossing

Who knows whose face did the man see first in the morning?

2

All I have guessed

are falling into place

Those incense sticks, the same frankincense, garlands and processions…

After the night is over

There will be meetings, for sure.

(Absentees’ have their names written on the paper

tied around the flower sticks)

All have come about in toto.

Their hearts have mellowed…

and, it is the opportune time.

If a hand of mine can stretch out

Can collect the cost of cremation.

In one corner,

my son on a ripped shirt,

with dry eyes

and clenched teeth

has placed himself like a ruffled sack.

Shame on you, my halfwit son!

Is it your act of valour!

The winter has just begun

Is it good for us to shiver!

Take away the flowers

They hurt me

The wreaths in heaps will harden into a hill

The flowers in heaps will harden into stone.

Remove the stone

It hurts me.

3

Since men

make the flowers tell too much of lies

I have no affinity for flowers.

Rather my choice is

the specks of fire

that never make a mask for man.

That it would happen

I knew for certain

That the foams of love would overflow someday

I knew for certain

No matter where in my heart

I have stored my love

they will be with me.

Night after night I stayed awake

To see when and how the days broke

My whole day had been on the go

To solve the mystery of darkness.

Not for a single day, nor for a moment

I ever paused.

Extracted from life

I poured the nectar into the pots kept in my heart

The nectar is spilling over today.

No

I am not content with the words spoken;

In the elements of the source

from where all the words transpire

And of the place where they finally go

I want to blend myself.

Change your shoulder.

Now

let the stacked woods take me.

let a dazzling speck of fire

caress me to forget

all the hurts caused by the flowers.

And yet, in sharp contrast to this exceptional brilliance, Subhas miserably faltered in the same act when he wrote for his hero, Joseph Stalin:

Comrade Stalin, Tumi

Comrade Stalin,

Happily, you sleep

The night is on the way out

Now we will stay awake…

From today,

the name of undying life is

Comrade Stalin

Subhas, knowingly or otherwise, joined Pablo Neruda, the last century’s most admired poet and loathed the man who had lead the pack of Stalin’s fan boys. But the poem holds no poetical merit like Neruda’s one, that reads:

To be men! That is the Stalinist law! . . .

We must learn from Stalin

his sincere intensity

his concrete clarity. . .

Stalin is the noon,

the maturity of man and the peoples.

Stalinists, Let us bear this title with pride. . . .

Khadyo Andolon (Food Movement) rocked the late 1950s. Subhas soon diversified into prose writing with no visible discomfort. His prose testified to the consummate flair of a seasoned writer with venerable insights and psychosocial observation. Beginning with a travelogue named ‘Amar Bangla’ (1951), ‘Akkhore Akkhore’ (1954), and ‘Kothar Kotha’ (1955), he went on to present, on one hand, simple yet lucid narratives on the life lived in the wilderness, and on the other hand his nuggets of thoughts about the Bangla language. Nihar Ranjan Das, an eminent scholar and art historian, wrote in the foreword of ‘Amar Bangla’, “He embarked on modern Bangla literature with his own incorruptible signature mark. He wandered like a dedicated foot soldier in the villages steeped in cold remoteness to know full well the life of the struggling people and their weal and woes, aspirations and despair, dreams and deprivations. It was his own quest to get rooted in rustic Bangaliana or Bengaliness. The years he thus spent in this self-styled exile from the cacophony of urban literature has gifted him with the rare rich virtues of empathy. This acquisition has built his one-of-its-kind identity. He is our solitary guide to this celebration of life, brought alive every day by those who provide our essential sustenance.” Curiously, he dedicated the travelogue to his comrade-in-arms, “Jolly Kaul, a son of Kashmir”, who was amongst the brightest erudite minds in the Red party.

In 1958, Subhas represented India at the Tashkent Conference of Afro–Asian Writers. He got to know a host of creative minds at play and consolidated his ideological marriage to Marxism, his unwavering admiration for Joseph Stalin, his commitment to the party and the people and his pronounced optimism for the ultimate freedom of all kinds of subjugations that formed his thematic priority over romantic predisposition. He wrote poems about the people rising from the centuries of forced sleep on the far horizon (…ghoom bhenge otha agnikone-e). He stood by them and proclaimed:

Lal Tuktuk Din

Digante kara amader sara peye

Saat ti ronger ghorai chapai jin

Tumi Alo, Ami andharer aal beye

Ante cholechhi lal tuk tuke din

(On the horizon, hearing our voice

they put a saddle on the horse of seven shades

You are the light, I, taking the alleys of darkness,

am out to bring the days of glowing red)

and:

Shokoler Gaan

Akasher chand dei bujhi haatchhani

O sob kebal bourgeois der maya

Amra to noi prajapati sandhani

Antato aaj madai na tar chhaya

(Does the moon seem to beckon from the sky

Those are all the fantasies of bourgeois

We are not the searchers of butterfly

Not in the least, we trample her umbra)

Channelising his passion through a strong political, social and psychological context, he also sarcastically greeted the poet pundits who were then helming the urban milieu of Bangla literature:

Hotobuddhi

If suddenly, our enemy fires shells from their cannon

I will say, ‘My boy, at any cost civilization, should go on

Closing my eyes then, I shall lend my ears to a singing cuckoo…

Contrary to being anti-romantic, Subhas nurtured his brand of romanticism. He was no less evocative when he put his trust in the power of love:

Hey, the puzzled soul, I understand

On the winding ways that you have lost

mirage has no resources to light a lamp

To my mind,

Come along this winding path

Changing our address, we will search for love

While the teachings of Marx and Engels weighed considerably in his work, the master of rhythm and metre that he was, had never allowed them to overpower his poetic beauty and nuances. Here is one more example of his signature quality:

You Hardly Cry

It’s a surprise,

You have hardly cried ever

The heartaches that you have left

packed in a tattered sack

in this home’s

every nook and corner

Is burning me with its heat

It is good in a way

My ears have gone deaf

Who says what, who wants more

Do not bother me anymore

In your tiny lawn at the end of the lane

Chili plants have flowered

When you will come back

In the sewing needle for torn clothes

In the glue for fixing the broken things

You exist

I feel you touching them

Taking the support of a walking stick

I wander limping from one room to another

Whenever we met

Overcoming my shyness, I could hardly tell

What I want to know, nevertheless

Never shedding your tears-

with a smile on your face, always

why have you saved all

monsoon rain in your pair of eyes!

Was it for flooding me

Overflowing all barriers!

Subhas, born exactly a hundred years ago as a Krishnanagrik (a beautiful coinage meaning Citizen of Krishnanagar, an old town in the Nadia district of West Bengal with an effervescent cultural tradition), denied himself of all kinds of material comfort and personal ambitions to be a part of the life “Babar Ali” and “Solomon’s mother” used to live in abject negligence and under social exclusion. Subhas ensured them immortality in his eponymous poem brewing strong empathy and a genuine spirit of protest:

Salemon-er Ma

The sky is looking like the eyes of insane Babarali.

Underneath, in a rally

that’s crossed five rail stations in a row

is seen lagging behind, time and gain,

Babarali’s daughter Salemon,

who is searching for her mother.

In the riddles of lanes and bylanes

of Kolkata

where are you hiding,

Salemon’s ma?

Where, where under the dazed sky

that’s looking like insane Babarali’s eyes

have you set up your home,

Salemon’s ma!

Hear, in sync with the chorus of

the rally

with eye boogers in the corners of her tearing eyes,

a voice calls you

Salemon’s ma…

The girl descending from the time of a famine

Stares another famine in her eyes

She is looking for you,

Only you, Salemon’s ma.

It is evident that from the late 1950s onwards, Subhash’s poetry had been evolving into something more introspective. The lyricism of “Phul phutuk na phutuk, aaj Boshonto”, and “Jato Durei Jai” carry two parallel processes of internalisation that he handled with equal deftness and dexterity:

Phool Phutuk Na Phutuk, Aj Boshonto

Whether the flowers bloom or do not bloom,

Today, It’s spring.

On the concrete footpath

with its feet immersed in stone

a dreary tree

full of young green leaves

is chucking

bursting its ribs

Whether the flowers bloom or do not bloom

Today, it’s spring.

Putting the black blinkers on the eyes of light

And removing them thereafter…

Laying men on the lap of death

And forgetting them thereafter…

The days that have passed along the street

Should never return.

In the afternoons anointed with turmeric

In lieu of one paisa or two

the ventriloquist boy who

went by airing the call of a cuckoo

…was taken away by the days long gone.

A nice tribute to the legendary philanthropic poet Subhash Mukhopadhyay . Passionately compiled and narrated .