It is really the story of how a young, mixed-race woman used paint to hold her own hand in a world that never fully held hers. In canvas after canvas, Amrita Sher-Gil turns solitude into a kind of slow-burning desire—desire for love, for artistic freedom, for a homeland that could contain all her contradictions. This is not just modern Indian art history; it is an early, radical chapter of feminist art, queer subtext, and the female gaze in Indian painting.

Letters from a lonely modernist

In her letters, she writes of cynicism, nihilism, and periods where only art and intense love affairs seemed to keep the void at bay. Those Paris years—studying at the École des Beaux-Arts, haunting cafés and studios—were filled with a restless need to test the limits of both sexuality and creativity.

What is striking in these letters is how lucid she is about sex, solitude, and art. She confides that channelling sexuality only into painting is “impossible,” insisting that her body’s needs and her brushstrokes are entangled, not opposed. When rumours circulate about a relationship with the painter Marie Louise Chassany, she neither fully denies desire nor apologises for exploring queer possibilities; instead she dissects the “disadvantages of relationships with men” with almost clinical clarity. The archive reveals a woman who refuses the sainted, sexless myth of the woman artist and insists that erotic life is part of artistic life—a stance that will later saturate her self-portraits.

Self-portrait as a room of one’s own

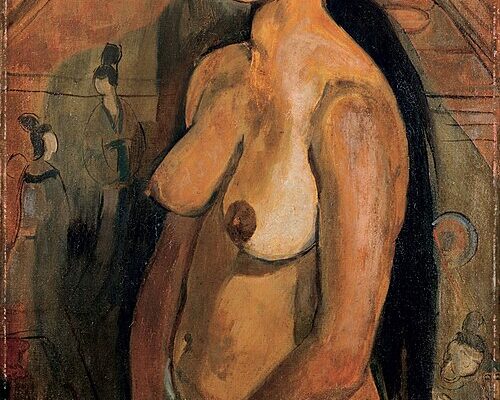

Search “Amrita Sher-Gil self-portrait” today and you are met with a litany of faces: frontal, three-quarter, eyes steady, backgrounds sparse. These portraits are like private rooms she builds inside the public museum, small sanctuaries where she can stage and re stage herself. In “Self-Portrait as a Tahitian” (1934), painted in Paris, she takes on the role of the colonial “other” that Gauguin fetishised, but occupies it on her own terms—part defiance, part masquerade.

Art historians note how she borrows from Gauguin and Van Gogh’s colour language while quietly undoing their gaze. The bare shoulders, crossed arms and intense red lips create a charged tableau; this is not a passive nude waiting to be consumed, but a woman who knows exactly what she is doing with her own image. The isolation of the figure—no lush Tahitian landscape, no attentive lover—heightens the erotics: the only relationship in the frame is between her and us, the viewers, and she refuses to let that relationship be simple.

Women alone together

Sher-Gil’s loneliness is never purely individual. When she returns to India and begins painting rural women—the iconic “Three Girls,” “Hill Women,” “Village Scene”—she turns the same inward gaze on bodies that Indian art had mostly cast as decorative or devotional. In these paintings, the women sit shoulder to shoulder yet seem emotionally elsewhere, caught in their own private weather of boredom, grief, or quiet resolve. The figures are often still, even “passive,” but critics now read that passivity as a language of protest: a refusal to perform happiness.

Archives and feminist scholars point out how these women mirror Amrita herself: suspended between expectation and desire, over determined by family, class, and patriarchy, yet possessed of an undeniable interior life. When we look back at her self-portraits after seeing these village scenes, the echo is impossible to miss. Her own face—unsmiling, slightly withdrawn, eyes heavy with thought—becomes one more “hill woman,” one more participant in the quiet solidarity of women whose loneliness is both structural and deeply intimate.

The erotic is not just about bodies

To call this “the erotics of isolation” is to stretch the word erotic back to its root in Eros: the life force that pulses underground, even when the surface looks still. Sher-Gil’s canvases rarely show overt seduction. Instead, desire appears as a tension between what the body knows and what the world allows. In “Self-Portrait as a Tahitian,” the crossed arms both conceal and draw attention to the chest; in “Three Girls,” tightly wrapped saris hint at curves that the colour fields refuse to fully reveal.

Her letters make clear that erotic life for her included men, possible relationships with women, and an almost mystical attachment to India itself. When she writes “India belongs only to me,” it reads like both a territorial claim and a love confession, as if her migration from Europe to India were a kind of romantic reunion. That possessive longing saturates her Indian period: the women she paints are not scenic ethnographic types but beloveds, mirrors, companions in solitude.

Why Amrita Sher-Gil still haunts search histories

Today, phrases like “Amrita Sher-Gil feminist artist,” “Amrita Sher-Gil self-portrait as Tahitian,” and “modern Indian art female gaze” keep pulling new viewers into her orbit. Her story fits the algorithmic hunger for keywords—woman artist, queer subtext, South Asian modernism—yet her paintings resist being flattened into hashtags. The more we read the archives, the more her loneliness looks less like tragic backstory and more like chosen ground: a room of her own carved out in paint, in which she could explore sexuality, identity, and melancholy without compromise.

For contemporary readers and art lovers scrolling between Frida Kahlo prints and Instagram selfies, Sher-Gil offers a different template for the self-portrait: not self-branding, but self-questioning. The erotics of isolation in her work asks a quiet but unsettling question—what if the most radical intimacy is not with a lover or a nation, but with one’s own gaze? To stand before her self-portrait is to feel that question settle on your skin, as if her loneliness has reached across decades and screens to touch the parts of you that also feel in-between, uncontained, and still fiercely, defiantly alive.

+ There are no comments

Add yours